- Home

- George MacDonald

Lilith Page 2

Lilith Read online

Page 2

I bethought me that a bird capable of addressing a man must have the right of a man to a civil answer; perhaps, as a bird, even a greater claim.

A tendency to croak caused a certain roughness in his speech, but his voice was not disagreeable, and what he said, although conveying little enlightenment, did not sound rude.

“I did not come through any door,” I rejoined.

“I saw you come through it!—saw you with my own ancient eyes!” asserted the raven, positively but not disrespectfully.

“I never saw any door!” I persisted.

“Of course not!” he returned; “all the doors you had yet seen—and you haven’t seen many—were doors in; here you came upon a door out! The strange thing to you,” he went on thoughtfully, “will be, that the more doors you go out of, the farther you get in!”

“Oblige me by telling me where I am.”

“That is impossible. You know nothing about whereness. The only way to come to know where you are is to begin to make yourself at home.”

“How am I to begin that where everything is so strange?”

“By doing something.”

“What?”

“Anything; and the sooner you begin the better! for until you are at home, you will find it as difficult to get out as it is to get in.”

“I have, unfortunately, found it too easy to get in; once out I shall not try again!”

“You have stumbled in, and may, possibly, stumble out again. Whether you have got in UNFORTUNATELY remains to be seen.”

“Do you never go out, sir?”

“When I please I do, but not often, or for long. Your world is such a half-baked sort of place, it is at once so childish and so self-satisfied—in fact, it is not sufficiently developed for an old raven—at your service!”

“Am I wrong, then, in presuming that a man is superior to a bird?”

“That is as it may be. We do not waste our intellects in generalising, but take man or bird as we find him.—I think it is now my turn to ask you a question!”

“You have the best of rights,” I replied, “in the fact that you CAN do so!”

“Well answered!” he rejoined. “Tell me, then, who you are—if you happen to know.”

“How should I help knowing? I am myself, and must know!”

“If you know you are yourself, you know that you are not somebody else; but do you know that you are yourself? Are you sure you are not your own father?—or, excuse me, your own fool?—Who are you, pray?”

I became at once aware that I could give him no notion of who I was. Indeed, who was I? It would be no answer to say I was who! Then I understood that I did not know myself, did not know what I was, had no grounds on which to determine that I was one and not another. As for the name I went by in my own world, I had forgotten it, and did not care to recall it, for it meant nothing, and what it might be was plainly of no consequence here. I had indeed almost forgotten that there it was a custom for everybody to have a name! So I held my peace, and it was my wisdom; for what should I say to a creature such as this raven, who saw through accident into entity?

“Look at me,” he said, “and tell me who I am.”

As he spoke, he turned his back, and instantly I knew him. He was no longer a raven, but a man above the middle height with a stoop, very thin, and wearing a long black tail-coat. Again he turned, and I saw him a raven.

“I have seen you before, sir,” I said, feeling foolish rather than surprised.

“How can you say so from seeing me behind?” he rejoined. “Did you ever see yourself behind? You have never seen yourself at all!—Tell me now, then, who I am.”

“I humbly beg your pardon,” I answered: “I believe you were once the librarian of our house, but more WHO I do not know.”

“Why do you beg my pardon?”

“Because I took you for a raven,” I said—seeing him before me as plainly a raven as bird or man could look.

“You did me no wrong,” he returned. “Calling me a raven, or thinking me one, you allowed me existence, which is the sum of what one can demand of his fellow-beings. Therefore, in return, I will give you a lesson:—No one can say he is himself, until first he knows that he IS, and then what HIMSELF is. In fact, nobody is himself, and himself is nobody. There is more in it than you can see now, but not more than you need to see. You have, I fear, got into this region too soon, but none the less you must get to be at home in it; for home, as you may or may not know, is the only place where you can go out and in. There are places you can go into, and places you can go out of; but the one place, if you do but find it, where you may go out and in both, is home.”

He turned to walk away, and again I saw the librarian. He did not appear to have changed, only to have taken up his shadow. I know this seems nonsense, but I cannot help it.

I gazed after him until I saw him no more; but whether distance hid him, or he disappeared among the heather, I cannot tell.

Could it be that I was dead, I thought, and did not know it? Was I in what we used to call the world beyond the grave? and must I wander about seeking my place in it? How was I to find myself at home? The raven said I must do something: what could I do here?—And would that make me somebody? for now, alas, I was nobody!

I took the way Mr. Raven had gone, and went slowly after him. Presently I saw a wood of tall slender pine-trees, and turned toward it. The odour of it met me on my way, and I made haste to bury myself in it.

Plunged at length in its twilight glooms, I spied before me something with a shine, standing between two of the stems. It had no colour, but was like the translucent trembling of the hot air that rises, in a radiant summer noon, from the sun-baked ground, vibrant like the smitten chords of a musical instrument. What it was grew no plainer as I went nearer, and when I came close up, I ceased to see it, only the form and colour of the trees beyond seemed strangely uncertain. I would have passed between the stems, but received a slight shock, stumbled, and fell. When I rose, I saw before me the wooden wall of the garret chamber. I turned, and there was the mirror, on whose top the black eagle seemed but that moment to have perched.

Terror seized me, and I fled. Outside the chamber the wide garret spaces had an UNCANNY look. They seemed to have long been waiting for something; it had come, and they were waiting again! A shudder went through me on the winding stair: the house had grown strange to me! something was about to leap upon me from behind! I darted down the spiral, struck against the wall and fell, rose and ran. On the next floor I lost my way, and had gone through several passages a second time ere I found the head of the stair. At the top of the great stair I had come to myself a little, and in a few moments I sat recovering my breath in the library.

Nothing should ever again make me go up that last terrible stair! The garret at the top of it pervaded the whole house! It sat upon it, threatening to crush me out of it! The brooding brain of the building, it was full of mysterious dwellers, one or other of whom might any moment appear in the library where I sat! I was nowhere safe! I would let, I would sell the dreadful place, in which an aërial portal stood ever open to creatures whose life was other than human! I would purchase a crag in Switzerland, and thereon build a wooden nest of one story with never a garret above it, guarded by some grand old peak that would send down nothing worse than a few tons of whelming rock!

I knew all the time that my thinking was foolish, and was even aware of a certain undertone of contemptuous humour in it; but suddenly it was checked, and I seemed again to hear the croak of the raven.

“If I know nothing of my own garret,” I thought, “what is there to secure me against my own brain? Can I tell what it is even now generating?—what thought it may present me the next moment, the next month, or a year away? What is at the heart of my brain? What is behind my THINK? Am I there at all?—Who, what am I?”

I could no more answer the question now than when the raven put it to me in—at—“Where in?—where at?” I said, and gave myself up as knowing anything

of myself or the universe.

I started to my feet, hurried across the room to the masked door, where the mutilated volume, sticking out from the flat of soulless, bodiless, non-existent books, appeared to beckon me, went down on my knees, and opened it as far as its position would permit, but could see nothing. I got up again, lighted a taper, and peeping as into a pair of reluctant jaws, perceived that the manuscript was verse. Further I could not carry discovery. Beginnings of lines were visible on the left-hand page, and ends of lines on the other; but I could not, of course, get at the beginning and end of a single line, and was unable, in what I could read, to make any guess at the sense. The mere words, however, woke in me feelings which to describe was, from their strangeness, impossible. Some dreams, some poems, some musical phrases, some pictures, wake feelings such as one never had before, new in colour and form—spiritual sensations, as it were, hitherto unproved: here, some of the phrases, some of the senseless half-lines, some even of the individual words affected me in similar fashion—as with the aroma of an idea, rousing in me a great longing to know what the poem or poems might, even yet in their mutilation, hold or suggest.

I copied out a few of the larger shreds attainable, and tried hard to complete some of the lines, but without the least success. The only thing I gained in the effort was so much weariness that, when I went to bed, I fell asleep at once and slept soundly.

In the morning all that horror of the empty garret spaces had left me.

CHAPTER IV. SOMEWHERE OR NOWHERE?

The sun was very bright, but I doubted if the day would long be fine, and looked into the milky sapphire I wore, to see whether the star in it was clear. It was even less defined than I had expected. I rose from the breakfast-table, and went to the window to glance at the stone again. There had been heavy rain in the night, and on the lawn was a thrush breaking his way into the shell of a snail.

As I was turning my ring about to catch the response of the star to the sun, I spied a keen black eye gazing at me out of the milky misty blue. The sight startled me so that I dropped the ring, and when I picked it up the eye was gone from it. The same moment the sun was obscured; a dark vapour covered him, and in a minute or two the whole sky was clouded. The air had grown sultry, and a gust of wind came suddenly. A moment more and there was a flash of lightning, with a single sharp thunder-clap. Then the rain fell in torrents.

I had opened the window, and stood there looking out at the precipitous rain, when I descried a raven walking toward me over the grass, with solemn gait, and utter disregard of the falling deluge. Suspecting who he was, I congratulated myself that I was safe on the ground-floor. At the same time I had a conviction that, if I were not careful, something would happen.

He came nearer and nearer, made a profound bow, and with a sudden winged leap stood on the window-sill. Then he stepped over the ledge, jumped down into the room, and walked to the door. I thought he was on his way to the library, and followed him, determined, if he went up the stair, not to take one step after him. He turned, however, neither toward the library nor the stair, but to a little door that gave upon a grass-patch in a nook between two portions of the rambling old house. I made haste to open it for him. He stepped out into its creeper-covered porch, and stood looking at the rain, which fell like a huge thin cataract; I stood in the door behind him. The second flash came, and was followed by a lengthened roll of more distant thunder. He turned his head over his shoulder and looked at me, as much as to say, “You hear that?” then swivelled it round again, and anew contemplated the weather, apparently with approbation. So human were his pose and carriage and the way he kept turning his head, that I remarked almost involuntarily,

“Fine weather for the worms, Mr. Raven!”

“Yes,” he answered, in the rather croaky voice I had learned to know, “the ground will be nice for them to get out and in!—It must be a grand time on the steppes of Uranus!” he added, with a glance upward; “I believe it is raining there too; it was, all the last week!”

“Why should that make it a grand time?” I asked.

“Because the animals there are all burrowers,” he answered, “—like the field-mice and the moles here.—They will be, for ages to come.”

“How do you know that, if I may be so bold?” I rejoined.

“As any one would who had been there to see,” he replied. “It is a great sight, until you get used to it, when the earth gives a heave, and out comes a beast. You might think it a hairy elephant or a deinotherium—but none of the animals are the same as we have ever had here. I was almost frightened myself the first time I saw the dry-bog-serpent come wallowing out—such a head and mane! and SUCH eyes!—but the shower is nearly over. It will stop directly after the next thunder-clap. There it is!”

A flash came with the words, and in about half a minute the thunder. Then the rain ceased.

“Now we should be going!” said the raven, and stepped to the front of the porch.

“Going where?” I asked.

“Going where we have to go,” he answered. “You did not surely think you had got home? I told you there was no going out and in at pleasure until you were at home!”

“I do not want to go,” I said.

“That does not make any difference—at least not much,” he answered. “This is the way!”

“I am quite content where I am.”

“You think so, but you are not. Come along.”

He hopped from the porch onto the grass, and turned, waiting.

“I will not leave the house to-day,” I said with obstinacy.

“You will come into the garden!” rejoined the raven.

“I give in so far,” I replied, and stepped from the porch.

The sun broke through the clouds, and the raindrops flashed and sparkled on the grass. The raven was walking over it.

“You will wet your feet!” I cried.

“And mire my beak,” he answered, immediately plunging it deep in the sod, and drawing out a great wriggling red worm. He threw back his head, and tossed it in the air. It spread great wings, gorgeous in red and black, and soared aloft.

“Tut! tut!” I exclaimed; “you mistake, Mr. Raven: worms are not the larvæ of butterflies!”

“Never mind,” he croaked; “it will do for once! I’m not a reading man at present, but sexton at the—at a certain graveyard—cemetery, more properly—in—at—no matter where!”

“I see! you can’t keep your spade still: and when you have nothing to bury, you must dig something up! Only you should mind what it is before you make it fly! No creature should be allowed to forget what and where it came from!”

“Why?” said the raven.

“Because it will grow proud, and cease to recognise its superiors.”

No man knows it when he is making an idiot of himself.

“Where DO the worms come from?” said the raven, as if suddenly grown curious to know.

“Why, from the earth, as you have just seen!” I answered.

“Yes, last!” he replied. “But they can’t have come from it first—for that will never go back to it!” he added, looking up.

I looked up also, but could see nothing save a little dark cloud, the edges of which were red, as if with the light of the sunset.

“Surely the sun is not going down!” I exclaimed, struck with amazement.

“Oh, no!” returned the raven. “That red belongs to the worm.”

“You see what comes of making creatures forget their origin!” I cried with some warmth.

“It is well, surely, if it be to rise higher and grow larger!” he returned. “But indeed I only teach them to find it!”

“Would you have the air full of worms?”

“That is the business of a sexton. If only the rest of the clergy understood it as well!”

In went his beak again through the soft turf, and out came the wriggling worm. He tossed it in the air, and away it flew.

I looked behind me, and gave a cry of dismay: I had but that

moment declared I would not leave the house, and already I was a stranger in the strange land!

“What right have you to treat me so, Mr. Raven?” I said with deep offence. “Am I, or am I not, a free agent?”

“A man is as free as he chooses to make himself, never an atom freer,” answered the raven.

“You have no right to make me do things against my will!”

“When you have a will, you will find that no one can.”

“You wrong me in the very essence of my individuality!” I persisted.

“If you were an individual I could not, therefore now I do not. You are but beginning to become an individual.”

All about me was a pine-forest, in which my eyes were already searching deep, in the hope of discovering an unaccountable glimmer, and so finding my way home. But, alas! how could I any longer call that house HOME, where every door, every window opened into OUT, and even the garden I could not keep inside!

I suppose I looked discomfited.

“Perhaps it may comfort you,” said the raven, “to be told that you have not yet left your house, neither has your house left you. At the same time it cannot contain you, or you inhabit it!”

“I do not understand you,” I replied. “Where am I?”

“In the region of the seven dimensions,” he answered, with a curious noise in his throat, and a flutter of his tail. “You had better follow me carefully now for a moment, lest you should hurt some one!”

“There is nobody to hurt but yourself, Mr. Raven! I confess I should rather like to hurt you!”

“That you see nobody is where the danger lies. But you see that large tree to your left, about thirty yards away?”

“Of course I do: why should I not?” I answered testily.

“Ten minutes ago you did not see it, and now you do not know where it stands!”

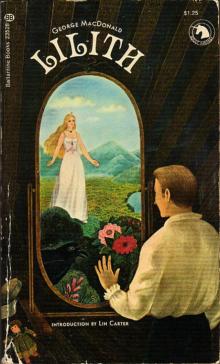

Lilith: A Romance

Lilith: A Romance The Princess and the Goblin

The Princess and the Goblin Phantastes: A Faerie Romance for Men and Women

Phantastes: A Faerie Romance for Men and Women A Double Story

A Double Story St. George and St. Michael

St. George and St. Michael Far Above Rubies

Far Above Rubies Lilith

Lilith