- Home

- George MacDonald

Lilith Page 12

Lilith Read online

Page 12

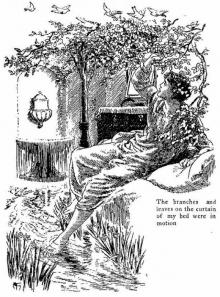

Several weeks had passed thus, when one night, after lying a long time awake, I rose, thinking to go out and breathe the cooler air; for, although from the running of the stream it was always fresh in the cave, the heat was not seldom a little oppressive. The moon outside was full, the air within shadowy clear, and naturally I cast a lingering look on my treasure ere I went. “Bliss eternal!” I cried aloud, “do I see her eyes?” Great orbs, dark as if cut from the sphere of a starless night, and luminous by excess of darkness, seemed to shine amid the glimmering whiteness of her face. I stole nearer, my heart beating so that I feared the noise of it startling her. I bent over her. Alas, her eyelids were close shut! Hope and Imagination had wrought mutual illusion! my heart’s desire would never be! I turned away, threw myself on the floor of the cave, and wept. Then I bethought me that her eyes had been a little open, and that now the awful chink out of which nothingness had peered, was gone: it might be that she had opened them for a moment, and was again asleep!—it might be she was awake and holding them close! In either case, life, less or more, must have shut them! I was comforted, and fell fast asleep.

That night I was again bitten, and awoke with a burning thirst.

In the morning I searched yet more thoroughly, but again in vain. The wound was of the same character, and, as before, was nearly well by the evening. I concluded that some large creature of the leech kind came occasionally from the hot stream. “But, if blood be its object,” I said to myself, “so long as I am there, I need hardly fear for my treasure!”

That same morning, when, having peeled a grape as usual and taken away the seeds, I put it in her mouth, her lips made a slight movement of reception, and I KNEW she lived!

My hope was now so much stronger that I began to think of some attire for her: she must be able to rise the moment she wished! I betook myself therefore to the forest, to investigate what material it might afford, and had hardly begun to look when fibrous skeletons, like those of the leaves of the prickly pear, suggested themselves as fit for the purpose. I gathered a stock of them, laid them to dry in the sun, pulled apart the reticulated layers, and of these had soon begun to fashion two loose garments, one to hang from her waist, the other from her shoulders. With the stiletto-point of an aloe-leaf and various filaments, I sewed together three thicknesses of the tissue.

During the week that followed, there was no farther sign except that she more evidently took the grapes. But indeed all the signs became surer: plainly she was growing plumper, and her skin fairer. Still she did not open her eyes; and the horrid fear would at times invade me, that her growth was of some hideous fungoid nature, the few grapes being nowise sufficient to account for it.

Again I was bitten; and now the thing, whatever it was, began to pay me regular visits at intervals of three days. It now generally bit me in the neck or the arm, invariably with but one bite, always while I slept, and never, even when I slept, in the daytime. Hour after hour would I lie awake on the watch, but never heard it coming, or saw sign of its approach. Neither, I believe, did I ever feel it bite me. At length I became so hopeless of catching it, that I no longer troubled myself either to look for it by day, or lie in wait for it at night. I knew from my growing weakness that I was losing blood at a dangerous rate, but I cared little for that: in sight of my eyes death was yielding to life; a soul was gathering strength to save me from loneliness; we would go away together, and I should speedily recover!

The garments were at length finished, and, contemplating my handiwork with no small satisfaction, I proceeded to mat layers of the fibre into sandals.

One night I woke suddenly, breathless and faint, and longing after air, and had risen to crawl from the cave, when a slight rustle in the leaves of the couch set me listening motionless.

“I caught the vile thing,” said a feeble voice, in my mother-tongue; “I caught it in the very act!”

She was alive! she spoke! I dared not yield to my transport lest I should terrify her.

“What creature?” I breathed, rather than said.

“The creature,” she answered, “that was biting you.”

“What was it?”

“A great white leech.”

“How big?” I pursued, forcing myself to be calm.

“Not far from six feet long, I should think,” she answered.

“You have saved my life, perhaps!—But how could you touch the horrid thing! How brave of you!” I cried.

“I did!” was all her answer, and I thought she shuddered.

“Where is it? What could you do with such a monster?”

“I threw it in the river.”

“Then it will come again, I fear!”

“I do not think I could have killed it, even had I known how!—I heard you moaning, and got up to see what disturbed you; saw the frightful thing at your neck, and pulled it away. But I could not hold it, and was hardly able to throw it from me. I only heard it splash in the water!”

“We’ll kill it next time!” I said; but with that I turned faint, sought the open air, but fell.

When I came to myself the sun was up. The lady stood a little way off, looking, even in the clumsy attire I had fashioned for her, at once grand and graceful. I HAD seen those glorious eyes! Through the night they had shone! Dark as the darkness primeval, they now outshone the day! She stood erect as a column, regarding me. Her pale cheek indicated no emotion, only question. I rose.

“We must be going!” I said. “The white leech——”

I stopped: a strange smile had flickered over her beautiful face.

“Did you find me there?” she asked, pointing to the cave.

“No; I brought you there,” I replied.

“You brought me?”

“Yes.”

“From where?”

“From the forest.”

“What have you done with my clothes—and my jewels?”

“You had none when I found you.”

“Then why did you not leave me?”

“Because I hoped you were not dead.”

“Why should you have cared?”

“Because I was very lonely, and wanted you to live.”

“You would have kept me enchanted for my beauty!” she said, with proud scorn.

Her words and her look roused my indignation.

“There was no beauty left in you,” I said.

“Why, then, again, did you not let me alone?”

“Because you were of my own kind.”

“Of YOUR kind?” she cried, in a tone of utter contempt.

“I thought so, but find I was mistaken!”

“Doubtless you pitied me!”

“Never had woman more claim on pity, or less on any other feeling!”

With an expression of pain, mortification, and anger unutterable, she turned from me and stood silent. Starless night lay profound in the gulfs of her eyes: hate of him who brought it back had slain their splendour. The light of life was gone from them.

“Had you failed to rouse me, what would you have done?” she asked suddenly without moving.

“I would have buried it.”

“It! What?—You would have buried THIS?” she exclaimed, flashing round upon me in a white fury, her arms thrown out, and her eyes darting forks of cold lightning.

“Nay; that I saw not! That, weary weeks of watching and tending have brought back to you,” I answered—for with such a woman I must be plain! “Had I seen the smallest sign of decay, I would at once have buried you.”

“Dog of a fool!” she cried, “I was but in a trance—Samoil! what a fate!—Go and fetch the she-savage from whom you borrowed this hideous disguise.”

“I made it for you. It is hideous, but I did my best.”

She drew herself up to her tall height.

“How long have I been insensible?” she demanded. “A woman could not have made that dress in a day!”

“Not in twenty days,” I rejoined, “hardly in thirty!”

“Ha! How long do you p

retend I have lain unconscious?—Answer me at once.”

“I cannot tell how long you had lain when I found you, but there was nothing left of you save skin and bone: that is more than three months ago.—Your hair was beautiful, nothing else! I have done for it what I could.”

“My poor hair!” she said, and brought a great armful of it round from behind her; “—it will be more than a three-months’ care to bring YOU to life again!—I suppose I must thank you, although I cannot say I am grateful!”

“There is no need, madam: I would have done the same for any woman—yes, or for any man either!”

“How is it my hair is not tangled?” she said, fondling it.

“It always drifted in the current.”

“How?—What do you mean?”

“I could not have brought you to life but by bathing you in the hot river every morning.”

She gave a shudder of disgust, and stood for a while with her gaze fixed on the hurrying water. Then she turned to me:

“We must understand each other!” she said. “—You have done me the two worst of wrongs—compelled me to live, and put me to shame: neither of them can I pardon!”

She raised her left hand, and flung it out as if repelling me. Something ice-cold struck me on the forehead. When I came to myself, I was on the ground, wet and shivering.

CHAPTER XX. GONE!—BUT HOW?

I rose, and looked around me, dazed at heart. For a moment I could not see her: she was gone, and loneliness had returned like the cloud after the rain! She whom I brought back from the brink of the grave, had fled from me, and left me with desolation! I dared not one moment remain thus hideously alone. Had I indeed done her a wrong? I must devote my life to sharing the burden I had compelled her to resume!

I descried her walking swiftly over the grass, away from the river, took one plunge for a farewell restorative, and set out to follow her. The last visit of the white leech, and the blow of the woman, had enfeebled me, but already my strength was reviving, and I kept her in sight without difficulty.

“Is this, then, the end?” I said as I went, and my heart brooded a sad song. Her angry, hating eyes haunted me. I could understand her resentment at my having forced life upon her, but how had I further injured her? Why should she loathe me? Could modesty itself be indignant with true service? How should the proudest woman, conscious of my every action, cherish against me the least sense of disgracing wrong? How reverently had I not touched her! As a father his motherless child, I had borne and tended her! Had all my labour, all my despairing hope gone to redeem only ingratitude? “No,” I answered myself; “beauty must have a heart! However profoundly hidden, it must be there! The deeper buried, the stronger and truer will it wake at last in its beautiful grave! To rouse that heart were a better gift to her than the happiest life! It would be to give her a nobler, a higher life!”

She was ascending a gentle slope before me, walking straight and steady as one that knew whither, when I became aware that she was increasing the distance between us. I summoned my strength, and it came in full tide. My veins filled with fresh life! My body seemed to become ethereal, and, following like an easy wind, I rapidly overtook her.

Not once had she looked behind. Swiftly she moved, like a Greek goddess to rescue, but without haste. I was within three yards of her, when she turned sharply, yet with grace unbroken, and stood. Fatigue or heat she showed none. Her paleness was not a pallor, but a pure whiteness; her breathing was slow and deep. Her eyes seemed to fill the heavens, and give light to the world. It was nearly noon, but the sense was upon me as of a great night in which an invisible dew makes the stars look large.

“Why do you follow me?” she asked, quietly but rather sternly, as if she had never before seen me.

“I have lived so long,” I answered, “on the mere hope of your eyes, that I must want to see them again!”

“You WILL not be spared!” she said coldly. “I command you to stop where you stand.”

“Not until I see you in a place of safety will I leave you,” I replied.

“Then take the consequences,” she said, and resumed her swift-gliding walk.

But as she turned she cast on me a glance, and I stood as if run through with a spear. Her scorn had failed: she would kill me with her beauty!

Despair restored my volition; the spell broke; I ran, and overtook her.

“Have pity upon me!” I cried.

She gave no heed. I followed her like a child whose mother pretends to abandon him. “I will be your slave!” I said, and laid my hand on her arm.

She turned as if a serpent had bit her. I cowered before the blaze of her eyes, but could not avert my own.

“Pity me,” I cried again.

She resumed her walking.

The whole day I followed her. The sun climbed the sky, seemed to pause on its summit, went down the other side. Not a moment did she pause, not a moment did I cease to follow. She never turned her head, never relaxed her pace.

The sun went below, and the night came up. I kept close to her: if I lost sight of her for a moment, it would be for ever!

All day long we had been walking over thick soft grass: abruptly she stopped, and threw herself upon it. There was yet light enough to show that she was utterly weary. I stood behind her, and gazed down on her for a moment.

Did I love her? I knew she was not good! Did I hate her? I could not leave her! I knelt beside her.

“Begone! Do not dare touch me,” she cried.

Her arms lay on the grass by her sides as if paralyzed.

Suddenly they closed about my neck, rigid as those of the torture-maiden. She drew down my face to hers, and her lips clung to my cheek. A sting of pain shot somewhere through me, and pulsed. I could not stir a hair’s breadth. Gradually the pain ceased. A slumberous weariness, a dreamy pleasure stole over me, and then I knew nothing.

All at once I came to myself. The moon was a little way above the horizon, but spread no radiance; she was but a bright thing set in blackness. My cheek smarted; I put my hand to it, and found a wet spot. My neck ached: there again was a wet spot! I sighed heavily, and felt very tired. I turned my eyes listlessly around me—and saw what had become of the light of the moon: it was gathered about the lady! she stood in a shimmering nimbus! I rose and staggered toward her.

“Down!” she cried imperiously, as to a rebellious dog. “Follow me a step if you dare!”

“I will!” I murmured, with an agonised effort.

“Set foot within the gates of my city, and my people will stone you: they do not love beggars!”

I was deaf to her words. Weak as water, and half awake, I did not know that I moved, but the distance grew less between us. She took one step back, raised her left arm, and with the clenched hand seemed to strike me on the forehead. I received as it were a blow from an iron hammer, and fell.

I sprang to my feet, cold and wet, but clear-headed and strong. Had the blow revived me? it had left neither wound nor pain!—But how came I wet?—I could not have lain long, for the moon was no higher!

The lady stood some yards away, her back toward me. She was doing something, I could not distinguish what. Then by her sudden gleam I knew she had thrown off her garments, and stood white in the dazed moon. One moment she stood—and fell forward.

A streak of white shot away in a swift-drawn line. The same instant the moon recovered herself, shining out with a full flash, and I saw that the streak was a long-bodied thing, rushing in great, low-curved bounds over the grass. Dark spots seemed to run like a stream adown its back, as if it had been fleeting along under the edge of a wood, and catching the shadows of the leaves.

“God of mercy!” I cried, “is the terrible creature speeding to the night-infolded city?” and I seemed to hear from afar the sudden burst and spread of outcrying terror, as the pale savage bounded from house to house, rending and slaying.

While I gazed after it fear-stricken, past me from behind, like a swift, all but noiseless arrow, shot a second

large creature, pure white. Its path was straight for the spot where the lady had fallen, and, as I thought, lay. My tongue clave to the roof of my mouth. I sprang forward pursuing the beast. But in a moment the spot I made for was far behind it.

“It was well,” I thought, “that I could not cry out: if she had risen, the monster would have been upon her!”

But when I reached the place, no lady was there; only the garments she had dropped lay dusk in the moonlight.

I stood staring after the second beast. It tore over the ground with yet greater swiftness than the former—in long, level, skimming leaps, the very embodiment of wasteless speed. It followed the line the other had taken, and I watched it grow smaller and smaller, until it disappeared in the uncertain distance.

But where was the lady? Had the first beast surprised her, creeping upon her noiselessly? I had heard no shriek! and there had not been time to devour her! Could it have caught her up as it ran, and borne her away to its den? So laden it could not have run so fast! and I should have seen that it carried something!

Horrible doubts began to wake in me. After a thorough but fruitless search, I set out in the track of the two animals.

CHAPTER XXI. THE FUGITIVE MOTHER

As I hastened along, a cloud came over the moon, and from the gray dark suddenly emerged a white figure, clasping a child to her bosom, and stooping as she ran. She was on a line parallel with my own, but did not perceive me as she hurried along, terror and anxiety in every movement of her driven speed.

“She is chased!” I said to myself. “Some prowler of this terrible night is after her!”

To follow would have added to her fright: I stepped into her track to stop her pursuer.

As I stood for a moment looking after her through the dusk, behind me came a swift, soft-footed rush, and ere I could turn, something sprang over my head, struck me sharply on the forehead, and knocked me down. I was up in an instant, but all I saw of my assailant was a vanishing whiteness. I ran after the beast, with the blood trickling from my forehead; but had run only a few steps, when a shriek of despair tore the quivering night. I ran the faster, though I could not but fear it must already be too late.

Lilith: A Romance

Lilith: A Romance The Princess and the Goblin

The Princess and the Goblin Phantastes: A Faerie Romance for Men and Women

Phantastes: A Faerie Romance for Men and Women A Double Story

A Double Story St. George and St. Michael

St. George and St. Michael Far Above Rubies

Far Above Rubies Lilith

Lilith